In March, we were still learning the new nouns. Pandemic. Quarantine. Distancing. Curve. Ventilator. In April, the words stop feeling borrowed and start feeling like furniture in the room.

And one word, in particular, has become a badge. A category. A moral sorting hat.

Essential.

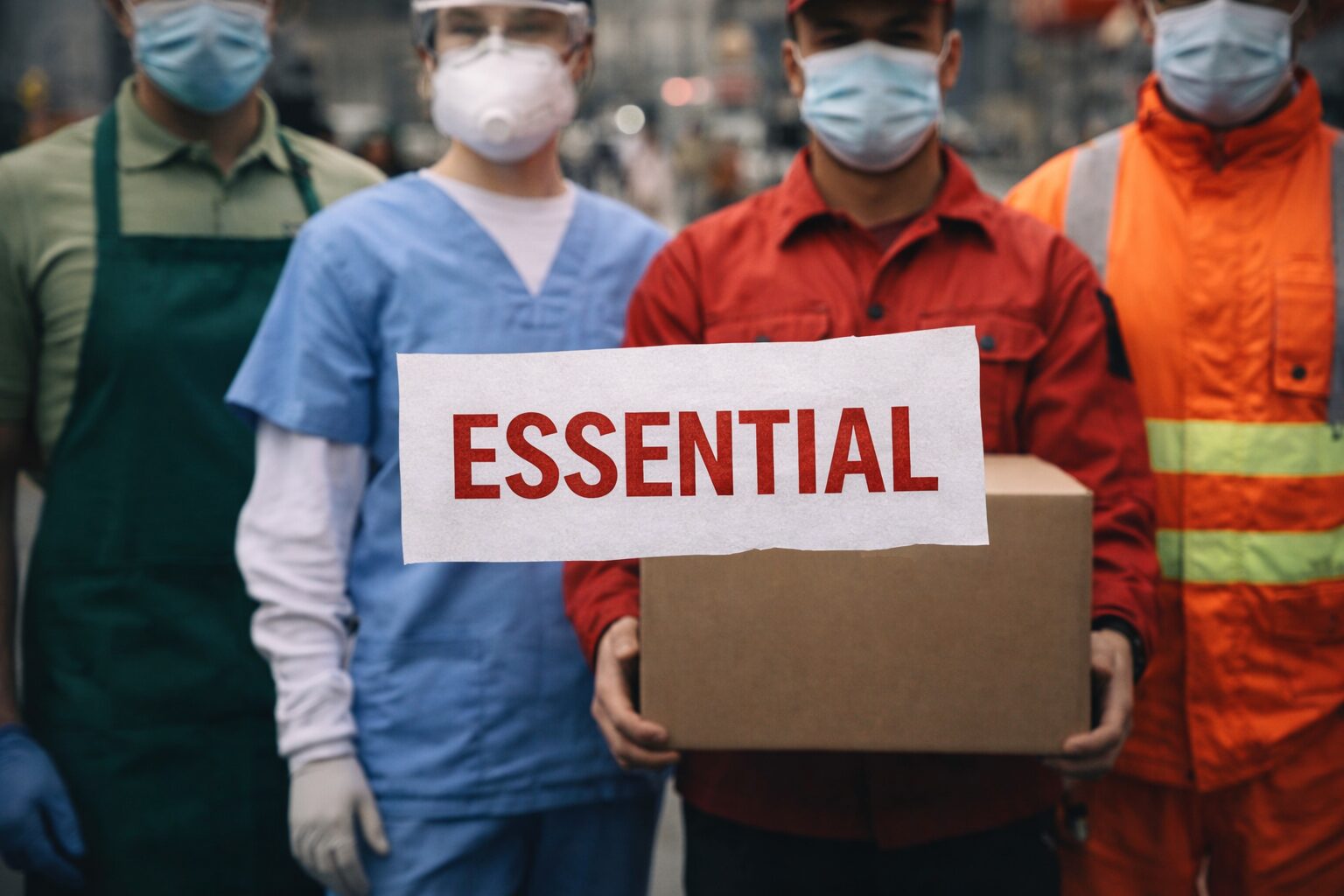

The phrase “essential worker” is supposed to honor people who keep the lights on. Nurses, grocery clerks, delivery drivers, cleaners, transit operators, warehouse staff, caregivers. The people who can’t mute life. The people whose jobs require presence. The people who are now required to stand between the rest of us and the chaos.

But the way we are using “essential” in April 2020 is not only honor. It’s a trick.

It’s a story we tell ourselves so we don’t have to admit what we’re doing.

A label is not protection

If someone is essential, the obvious conclusion is that they should be protected. They should be prioritized. They should be equipped. They should be paid like their risk matters. They should have the right to refuse unsafe conditions without losing their livelihood.

Instead, “essential” is being used as an incantation. Say it, and the moral math disappears.

We call a worker essential, and then we act as if their fear is optional. We praise them, and then we send them back into the same conditions. We clap, and then we treat protective gear like a luxury. We post about heroes, and then we shame people for asking for hazard pay.

Essential becomes a compliment that substitutes for policy.

It feels good to say. It costs less than doing.

The praise economy

April is full of performance. Yard signs, hashtags, applause at a set hour. A new kind of civic ritual where we honor essential workers by being visible about it.

I don’t hate this. Gratitude is not a sin.

But gratitude can be a cover.

The applause is a form of emotional outsourcing. It lets the rest of us feel aligned with the good without confronting the structure that creates the harm. It turns systemic vulnerability into a story of individual courage.

And courage is a convenient narrative. Courage implies choice. Courage implies heroism. Courage implies someone rising to the occasion.

Many essential workers did not choose heroism. They chose rent. They chose insurance. They chose groceries. They chose keeping their job because losing their job is not a moral failure, it’s a disaster.

When you frame necessity as heroism, you make exploitation look like inspiration.

Who gets to stay home

The pandemic has created a new social line. On one side, the people whose work can be done through a screen. On the other, the people whose work is physical. The people who touch things. The people who clean things. The people who deliver things. The people who make sure the first group can stay inside.

This line isn’t just about job type. It’s about safety. It’s about stability. It’s about the ability to refuse risk.

Working from home is not just a convenience. In April 2020, it’s a form of protection.

And protection is being distributed according to class.

This is not a conspiracy. It’s a design feature of an economy built to make some lives flexible and others disposable. The virus didn’t invent that. It just made it impossible to ignore.

The moral anesthetic of “we’re all in this together”

If you want to hear a phrase that is doing a lot of work this month, listen for it.

We’re all in this together.

It’s the kind of sentence that sounds like solidarity. It travels well. It comforts. It performs unity.

But it isn’t always true.

We are not all in the same risk. We are not all in the same housing. We are not all in the same access to health care. We are not all in the same ability to work remotely. We are not all in the same relationship to the state, or to enforcement, or to debt.

We are all in the same storm, maybe.

But we are not in the same boat.

The “together” line becomes an anesthetic when it is used to erase those differences. When it becomes a way to flatten inequality into a shared vibe. When it becomes a substitute for asking who is carrying the burden.

Essential as a political identity

There is another reason “essential” is dangerous as a label. It can become an identity that the system weaponizes.

If you are essential, you are supposed to be proud. You are supposed to be tough. You are supposed to “step up.” Your hesitation becomes selfish. Your fear becomes weakness. Your request for protection becomes ingratitude.

The label creates pressure. It turns workers into symbols. And symbols don’t get to be complicated.

This is what the attention economy does best. It takes human lives and compresses them into simple archetypes. Heroes, cowards, patriots, traitors. In April 2020, we are doing that to people who are just trying to survive.

What respect looks like

If “essential worker” is going to mean anything besides a feel-good caption, it has to become a contract.

Respect looks like equipment. Respect looks like clear safety standards. Respect looks like paid sick leave that doesn’t punish people for getting sick. Respect looks like hazard pay, not as charity, but as recognition of risk. Respect looks like enforcement aimed at employers, not only at individuals.

Respect looks like a culture that stops pretending that applause is enough.

The story we tell after April

When this is over, America will tell itself stories. It always does.

It will tell a story about resilience. About unity. About heroism. About the way we pulled together.

Some of that will be true.

But the deeper story will be about what we normalized. About which lives we treated as expendable. About how quickly we turned moral praise into a substitute for material protection. About how we learned to call people essential while treating them as replaceable.

April 2020 is a mirror.

The question is whether we can look into it without flinching.

Because if “essential” is just a compliment, then it is not honor.

It is camouflage.

Leave a Reply